|

|

|

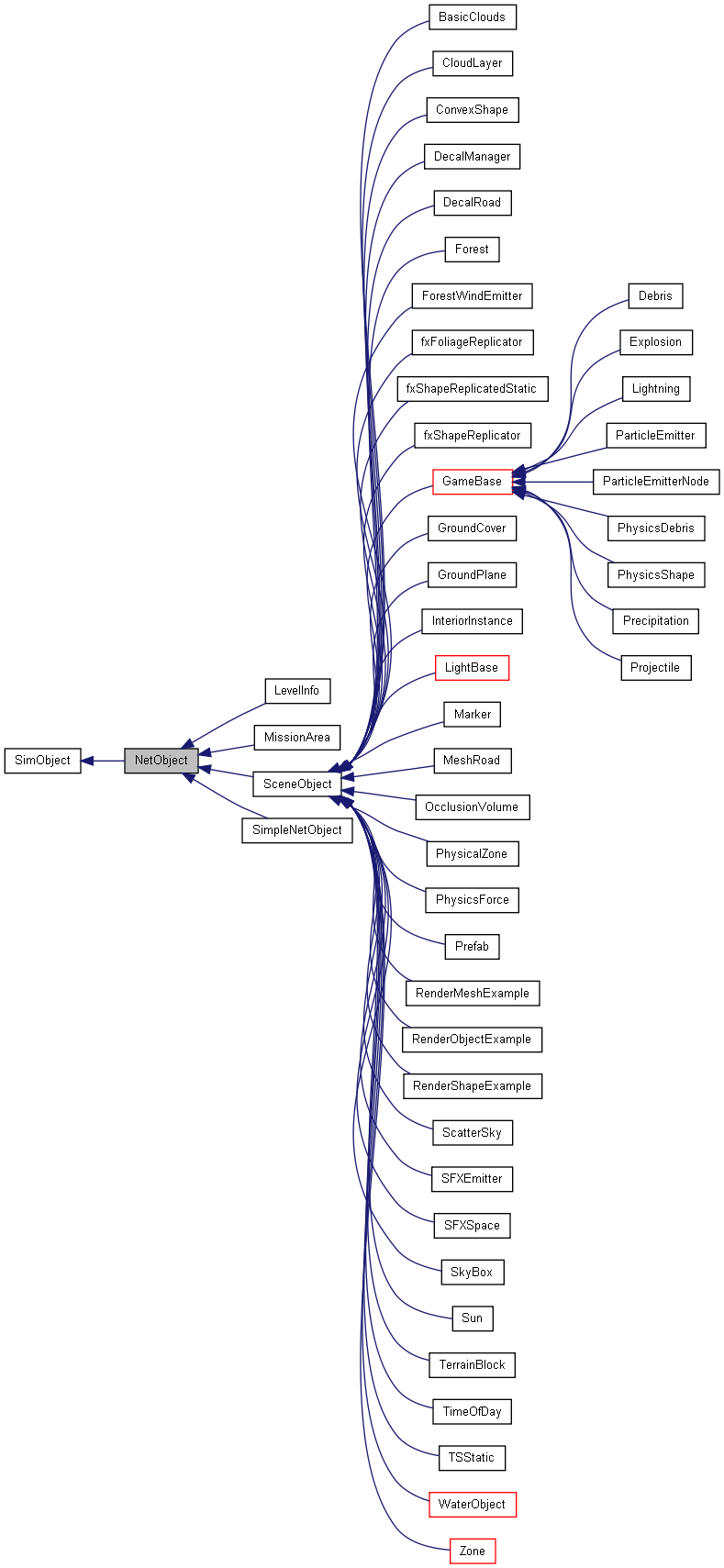

NetObject Class Reference

[Networking]

Superclass for all ghostable networked objects. More...

Public Member Functions | |

| void | clearScopeToClient (NetConnection client) |

| Undo the effects of a scopeToClient() call. | |

| int | getClientObject () |

| Returns a pointer to the client object when on a local connection. | |

| int | getGhostID () |

| Get the ghost index of this object from the server. | |

| int | getServerObject () |

| Returns a pointer to the client object when on a local connection. | |

| bool | isClientObject () |

| Called to check if an object resides on the clientside. | |

| bool | isServerObject () |

| Checks if an object resides on the server. | |

| void | scopeToClient (NetConnection client) |

| Cause the NetObject to be forced as scoped on the specified NetConnection. | |

| void | setScopeAlways () |

| Always scope this object on all connections. | |

Detailed Description

Superclass for all ghostable networked objects.

Introduction To NetObject And Ghosting

This class is the basis of the ghost implementation in Torque 3D. Every 3D object is a NetObject. One of the most powerful aspects of Torque's networking code is its support for ghosting and prioritized, most-recent-state network updates. The way this works is a bit complex, but it is immensely efficient. Let's run through the steps that the server goes through for each client in this part of Torque's networking:

- First, the server determines what objects are in-scope for the client. This is done by calling onCameraScopeQuery() on the object which is considered the "scope" object. This is usually the player object, but it can be something else. (For instance, the current vehicle, or a object we're remote controlling.)

- Second, it ghosts them to the client; this is implemented in netGhost.cc.

- Finally, it sends updates as needed, by checking the dirty list and packing updates.

There several significant advantages to using this networking system:

- Efficient network usage, since we only send data that has changed. In addition, since we only care about most-recent data, if a packet is dropped, we don't waste effort trying to deliver stale data.

- Cheating protection; since we don't deliver information about game objects which aren't in scope, we dramatically reduce the ability of clients to hack the game and gain a meaningful advantage. (For instance, they can't find out about things behind them, since objects behind them don't fall in scope.) In addition, since ghost IDs are assigned per-client, it's difficult for any sort of co-ordination between cheaters to occur.

NetConnection contains the Ghost Manager implementation, which deals with transferring data to the appropriate clients and keeping state in synch.

- See also:

- On Ghosting and Scoping for a description of the ghosting system.

An Example Implementation

The basis of the ghost implementation in Torque is NetObject. It tracks the dirty flags for the various states that the object wants to network, and does some other book-keeping to allow more efficient operation of the networking layer.

Using a NetObject is very simple; let's go through a simple example implementation:

class SimpleNetObject : public NetObject { public: typedef NetObject Parent; DECLARE_CONOBJECT(SimpleNetObject);

Above is the standard boilerplate code for a Torque class. You can find out more about this in SimObject.

char message1[256]; char message2[256]; enum States { Message1Mask = BIT(0), Message2Mask = BIT(1), };

For our example, we're having two "states" that we keep track of, message1 and message2. In a real object, we might map our states to health and position, or some other set of fields. You have 32 bits to work with, so it's possible to be very specific when defining states. In general, you should try to use as few states as possible (you never know when you'll need to expand your object's functionality!), and in fact, most of your fields will end up changing all at once, so it's not worth it to be too fine-grained. (As an example, position and velocity on Player are controlled by the same bit, as one rarely changes without the other changing, too.)

SimpleNetObject() { // In order for an object to be considered by the network system, // the Ghostable net flag must be set. // The ScopeAlways flag indicates that the object is always scoped // on all active connections. mNetFlags.set(ScopeAlways | Ghostable); dStrcpy(message1, "Hello World 1!"); dStrcpy(message2, "Hello World 2!"); }

Here is the constructor. Here, you see that we initialize our net flags to show that we should always be scoped, and that we're to be taken into consideration for ghosting. We also provide some initial values for the message fields.

U32 packUpdate(NetConnection *, U32 mask, BitStream *stream) { // check which states need to be updated, and update them if(stream->writeFlag(mask & Message1Mask)) stream->writeString(message1); if(stream->writeFlag(mask & Message2Mask)) stream->writeString(message2); // the return value from packUpdate can set which states still // need to be updated for this object. return 0; }

Here's half of the meat of the networking code, the packUpdate() function. (The other half, unpackUpdate(), we'll get to in a second.) The comments in the code pretty much explain everything, however, notice that the code follows a pattern of if(writeFlag(mask & StateMask)) { ... write data ... }. The packUpdate()/unpackUpdate() functions are responsible for reading and writing the dirty bits to the bitstream by themselves.

void unpackUpdate(NetConnection *, BitStream *stream) { // the unpackUpdate function must be symmetrical to packUpdate if(stream->readFlag()) { stream->readString(message1); Con::printf("Got message1: %s", message1); } if(stream->readFlag()) { stream->readString(message2); Con::printf("Got message2: %s", message2); } }

The other half of the networking code in any NetObject, unpackUpdate(). In our simple example, all that the code does is print the new messages to the console; however, in a more advanced object, you might trigger animations, update complex object properties, or even spawn new objects, based on what packet data you unpack.

void setMessage1(const char *msg) { setMaskBits(Message1Mask); dStrcpy(message1, msg); } void setMessage2(const char *msg) { setMaskBits(Message2Mask); dStrcpy(message2, msg); }

Here are the accessors for the two properties. It is good to encapsulate your state variables, so that you don't have to remember to make a call to setMaskBits every time you change anything; the accessors can do it for you. In a more complex object, you might need to set multiple mask bits when you change something; this can be done using the | operator, for instance, setMaskBits( Message1Mask | Message2Mask ); if you changed both messages.

IMPLEMENT_CO_NETOBJECT_V1(SimpleNetObject); ConsoleMethod(SimpleNetObject, setMessage1, void, 3, 3, "(string msg) Set message 1.") { object->setMessage1(argv[2]); } ConsoleMethod(SimpleNetObject, setMessage2, void, 3, 3, "(string msg) Set message 2.") { object->setMessage2(argv[2]); }

Finally, we use the NetObject implementation macro, IMPLEMENT_CO_NETOBJECT_V1(), to implement our NetObject. It is important that we use this, as it makes Torque perform certain initialization tasks that allow us to send the object over the network. IMPLEMENT_CONOBJECT() doesn't perform these tasks, see the documentation on AbstractClassRep for more details.

- See also:

- SimpleNetObject

- NetConnection

- SceneObject

Member Function Documentation

| void NetObject::clearScopeToClient | ( | NetConnection | client | ) |

Undo the effects of a scopeToClient() call.

- Parameters:

-

client The connection to remove this object's scoping from

- See also:

- scopeToClient()

| int NetObject::getClientObject | ( | ) |

Returns a pointer to the client object when on a local connection.

Short-Circuit-Networking: this is only valid for a local-client / singleplayer situation.

- Returns:

- the SimObject ID of the client object.

- Example:

// Psuedo-code, some values left out for this example %node = new ParticleEmitterNode(){}; %clientObject = %node.getClientObject(); if(isObject(%clientObject) %clientObject.setTransform("0 0 0");

- See also:

- Local Connections

| int NetObject::getGhostID | ( | ) |

Get the ghost index of this object from the server.

- Returns:

- The ghost ID of this NetObject on the server

- Example:

%ghostID = LocalClientConnection.getGhostId( %serverObject );

| int NetObject::getServerObject | ( | ) |

Returns a pointer to the client object when on a local connection.

Short-Circuit-Netorking: this is only valid for a local-client / singleplayer situation.

- Returns:

- The SimObject ID of the server object.

- Example:

// Psuedo-code, some values left out for this example %node = new ParticleEmitterNode(){}; %serverObject = %node.getServerObject(); if(isObject(%serverObject) %serverObject.setTransform("0 0 0");

- See also:

- Local Connections

| bool NetObject::isClientObject | ( | ) |

Called to check if an object resides on the clientside.

- Returns:

- True if the object resides on the client, false otherwise.

| bool NetObject::isServerObject | ( | ) |

Checks if an object resides on the server.

- Returns:

- True if the object resides on the server, false otherwise.

| void NetObject::scopeToClient | ( | NetConnection | client | ) |

Cause the NetObject to be forced as scoped on the specified NetConnection.

- Parameters:

-

client The connection this object will always be scoped to

- Example:

// Called to create new cameras in TorqueScript // %this - The active GameConnection // %spawnPoint - The spawn point location where we creat the camera function GameConnection::spawnCamera(%this, %spawnPoint) { // If this connection's camera exists if(isObject(%this.camera)) { // Add it to the mission group to be cleaned up later MissionCleanup.add( %this.camera ); // Force it to scope to the client side %this.camera.scopeToClient(%this); } }

- See also:

- clearScopeToClient()

| void NetObject::setScopeAlways | ( | ) |

Always scope this object on all connections.

The object is marked as ScopeAlways and is immediately ghosted to all active connections. This function has no effect if the object is not marked as Ghostable.